A One-of-a-Kind Gene Therapy: How Scientists Edited a Baby’s DNA to Treat a Fatal Metabolic Disorder

- Daksha Chandragiri

- Dec 12, 2025

- 4 min read

This blog post serves to simplify the scholarly article “Patient-Specific in Vivo Gene Editing to Treat a Rare Genetic Disease” by Kiran Musunuru from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the University of Pennsylvania.

Within 48 hours of birth, a baby boy's life hung in the balance. His body couldn't process ammonia, a toxic byproduct that was poisoning his brain with every feeding. Standard treatments could only buy time, and a liver transplant would take far too long.

Until a team at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia decided to rewrite his DNA.

The Diagnoses

The patient in this study was diagnosed with CPS1 deficiency within 48 hours of being born. Carbomyl-phosphate synthetase 1 (CPS1) deficiency is a urea cycle disorder that prevents the body from removing ammonia, a toxic byproduct of protein digestion. This disorder is caused by mutations in the CPS1 gene and is an autosomal recessive disorder, meaning that the baby has inherited two defective genes, one from each parent. This specific mutation is almost like a DNA “typo” that tells cells to stop making the CPS1 enzyme too early, resulting in a nonfunctional protein. Because the enzyme can’t function normally, the body is unable to convert the ammonia into urea, which allows for the safe excretion through the urinary system. This buildup of ammonia in the blood, called hyperammonemia, is toxic to the brain and can lead to symptoms like vomiting, seizures, brain swelling, and death if untreated.

Standard protocol for such an illness was a protein-restricted diet and the use of nitrogen-scavenging drugs to control the ammonia levels in the bloodstream. Liver transplants are the only cure, but infants are often not stable enough to survive the wait. Doctors could only try to keep the baby alive with treatments that focused on the symptoms until a liver transplant surgery could be performed, but it was a race against time that was often a losing one.

The research

The scientists' question: “Can we design a personalized gene-editing treatment, created specifically for one patient’s unique mutation, that safely repairs the gene inside their own liver cells?”

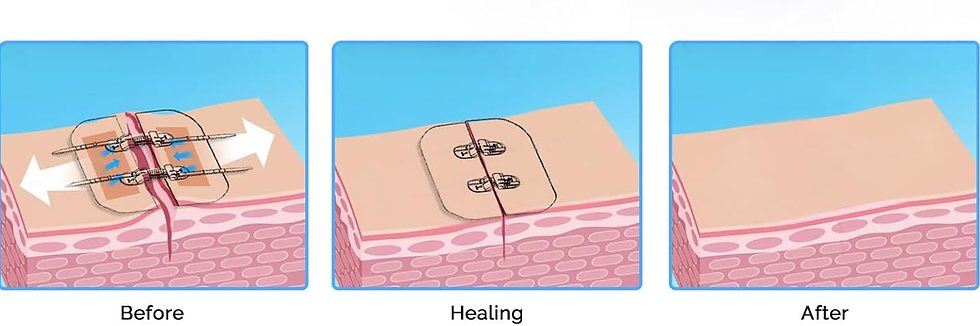

They began by designing the custom therapy. Based on genetic testing done on the sick baby, they found a Q335X mutation in the CPS1 gene. This mutated gene has a T nucleotide where there should be a C nucleotide. If there were a C, it would’ve led to the continuous coding of the CPS1 enzyme, but the presence of a T resulted in a premature stop codon. The scientists identified that they needed to create a base editing enzyme to change the A nucleotide on the opposite DNA strand to a G nucleotide. This may seem counterintuitive, but DNA strands always pair in predictable ways: A pairs with T, and C pairs with G. By fixing the A→G on the opposite strand, the cell recognizes the mismatch and naturally restores the correct C on the mutated strand during transcription. In other words, editing the “partner” base triggers the cell to rebuild the correct sequence and recover the functional CPS1 gene and product. To achieve this, they created an adenine base editor (ABE)—a protein-RNA complex—but they needed a way for this enzyme to find the mutation.

The scientists then needed to create a guide RNA (gRNA). This nucleic acid acts like a GPS, telling the base editor to go here, change this DNA letter, and to do it fast. They analyzed the DNA sequence surrounding the mutation and then synthesized the correct gRNA to successfully get the ABE to the Q335X mutation.

The next step was to figure out the perfect delivery method into the body. Because the CPS1 enzyme works almost exclusively in liver cells, the scientists needed to get the gene-editing tools into the hepatocytes efficiently. They used lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) to deliver the gRNA and ABE into the liver because LNPs are one of the safest and most effective ways to transport delicate gene-editing molecules. This method was chosen because hepatocytes readily absorb lipid-based particles as the liver filters blood, and LNPs can safely transport fragile RNAs that would otherwise degrade instantly.

After testing the treatment in cell models and animal studies to confirm that it could edit the gene accurately and safely, the team received the FDA’s approval for an emergency single-patient use to start treating the baby. Six months after the baby was born, they gave the baby two infusions, each one month apart. After the first dose, which was very low, they saw no critical symptoms or adverse effects, so they proceeded to a higher dosage the second time. After both, the team observed several improved outcomes: the baby’s ammonia levels fell from a near fatal 23 μmol/L to a normal reading of 13 μmol/L, the protein tolerance improved, and the dosage of nitrogen scavenging medication was cut by half. These changes indicated that even a small percentage of corrected liver cells restored enough CPS1 enzyme activity to significantly protect against life-threatening hyperammonemia.

What does this mean for the future of in-vivo gene editing?

This personalized gene-editing therapy marks a turning point in how we approach rare genetic diseases. Instead of managing symptoms or waiting for a transplant, clinicians corrected the root mutation directly inside the patient’s liver cells. The success of this case suggests that future treatments could be rapidly customized for other rare disorders simply by changing the gRNA while keeping the same delivery methods.

.png)