Using 3D-Printers to Engineer Bone Tissue

- Nabiha Kashfee

- Nov 29, 2025

- 10 min read

This blog post serves to simplify this scholarly paper:

3D-printed polymeric biomaterials in bone tissue engineering, published in the Biomedical Materials Journal by Tianyi Xia, Xianglong Zhou, Haoran Zhou, Jiheng Xiao, Jianhui Xiang, Hanhong Fang, Liming Xiong, and Fan Ding.

Boney Problems

Far from being static, each bone in our body acts as a living, active tissue; always being broken down and rebuilt to maintain strength and function. But when the formation of new tissue can’t keep up with the breakdown of old bone, problems start to occur. One example is osteoporosis, where bone becomes so brittle that even the simplest movements, such as bending over, can lead to a fracture. Most severe osteoporosis related breaks usually occur in the spine or the hip. Crushed vertebrae in the spine can lead to chronic pain, height loss, or a hunched posture, while hip fractures can cause disability and even increase the risk of death.

Another widespread condition in the elderly population is osteoarthritis, which develops when the cartilage that protects the ends of bone gradually degenerates. This can affect any joint on the body but is mainly present in the spine, hips, hands, and knees. Without the cartilage, the bones rub directly against each other causing pain, stiffness, swelling, and even loss of mobility. The progression of this disease can make it difficult to perform simple actions such as walking or even standing up, reducing the quality of life.

What is Bone Tissue Engineering (BTE)?

As the global population ages, the incidence of bone defects, fractures, and degenerative skeletal disorders continue to rise. While traditional bone grafts and metal implants are effective in bone repair, they often fall short when it comes to restoring full strength or function. In order to meet the increasing clinical demand, scientists have turned to an emerging field: bone tissue engineering (BTE).

A type of tissue engineering, the purpose of BTE is to regenerate bone tissues so that damaged bones can be supported or replaced in a way that naturally integrates to the body. This process relies on the combined use of biocompatible scaffolds, living cells, and biochemical signals to stimulate new bone growth. In recent years, 3D printing, an additive manufacturing process, has become an important tool in this field, allowing scientists to design customized scaffolds that match a patient’s anatomy and provide the precise structure for cells to grow. The end goal is to not only restore structure but also encourage the development of nerves and blood vessels, creating a fully functional bone.

Traditional Bone Repair

Severe bone defects usually require surgical procedures for treatment. The most common treatment is bone grafting which involves transplanting bone from elsewhere to repair bone loss, fractures, or defects. There are several grafting techniques currently in use, the main one being autografting: bone tissue is extracted from the patient's lower body, usually from the ridge of the hip bone, upper part of the shin bone, or the lower part of the thigh bone, and then transplanted to the site of the defect. This method encourages natural bone growth and has good tissue and immune compatibility because the graft material comes from the same body.

Alternative methods include allogeneic grafting, where the graft material is taken from a human donor, or even xenogeneic grafting, which uses bone from other species such as pigs or bovines.

Limits of the Old Methods

Even though grafting is usually successful, the traditional methods face many obstacles. The procedures themselves are highly invasive and can take up to a year for full recovery and integration. Donor bone is also limited, which means not every patient can receive the ideal graft, and grafts from other humans and even animals carry a high risk of immune rejection and disease transmission, since the material comes from another body. On top of that, the graft and host bone do not always fuse properly, especially in large or irregular defects, which can lead to instability, delayed healing, or complete graft failure.

In the most severe cases, this can result in repeated surgeries, chronic pain, infection, or permanent loss of function. For patients with major trauma, cancer-related bone loss, or degenerative diseases, these limitations can make traditional grafting inadequate or dangerous.

Modern Breakthroughs: 3D-Printed Polymeric Scaffolds

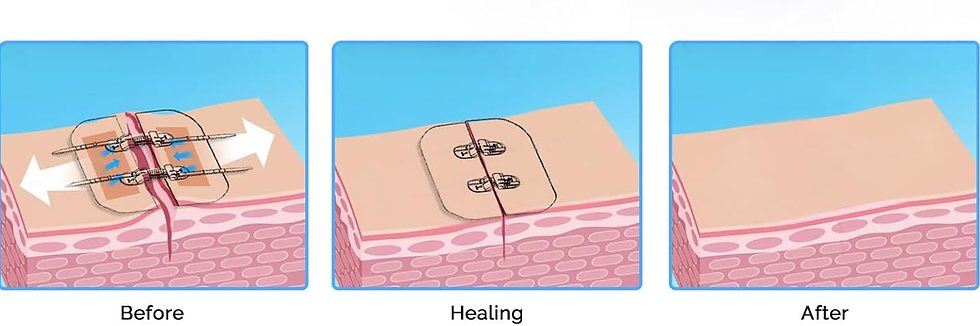

In order to overcome the limitations of grafting, researchers began developing materials that could naturally support bone regeneration. Unlike metal implants or donor grafts, they can be printed to match the patient’s bone structure. As the patient recovers, the scaffold gradually degrades until it is absorbed back into the body, leaving behind fully, functional bone tissue.

But how does this advanced technology actually work?

Scientists used 3D printing to create polymeric scaffolds; synthetic frameworks that act as temporary support for new bone growth.

These scaffolds provide both the strength and environment needed for bone repair. Their pores allow growth factors, nutrients, and other signaling molecules to reach cells, while their polymer composition ensures that the structure is compatible with the body.

What makes these Implants Special?

The implants made with 3D printing have to meet a few requirements:

Provide a framework for bone cells to grow on.

Stimulate new bone formation by turning stem cells into bone cells.

Form a stable, lasting connection with the surrounding natural bone.

Be biologically compatible with the host body.

Avoid triggering the immune response.

Maintain chemical and mechanical stability in the host body.

When designing the 3D printed grafts, scientists have to choose nanocomposite biomaterials that mimic natural bone. These materials must meet three criteria:

Porosity: The material should have interconnected pores to allow bone cells to grow, allow nutrient and oxygen flow, and support blood vessel formation. This ensures that the new bone tissue develops throughout the scaffold rather than only on the surface because bone cells are allowed to migrate and attach to different areas.

Mechanical Strength: Since bone provides structural support, the material needs to have a high load-bearing capacity to withstand stress that can occur during daily activities like walking. It also provides stability to the site of injury.

Biocompatibility: All materials must be safe for the body, causing no immune reaction or inflammation. This allows the material to integrate naturally with the surrounding bone and tissues.

Polymers are a popular choice because they satisfy all three requirements and can be easily customized for each patient.

The polymers can be natural or derived from artificial synthesis. They should also be easy to obtain and cost effective so they can be mass produced.

Table 1. Natural polymers that are ideal for BTE:

Polymer | Source | Key Properties | Role in BTE |

Chitosan | Chitin from exoskeletons of organism | High biocompatibility, moderate porosity, can take weeks to months to degrade, moderate mechanical strength | Provides scaffold for bone cell growth and makes new bone |

Gelatin | Denatured collagen | High biocompatibility, moderate porosity, can take weeks to degrade, low mechanical strength | Promotes cell adhesion, multiplication, and growth |

Alginate | Brown algae cell walls | High biocompatibility, high porosity, can take weeks to months to degrade, high mechanical strength | Provides 3D support for cells; used in bioinks for printing |

Cellulose | Cell wall of plants | High biocompatibility, moderate porosity, can take months to years to degrade, high mechanical strength | Provides strength and porous structure which supports cell attachment and nutrient flow |

Collagen | Animal connective tissue | High biocompatibility, moderate porosity, can take months to a year to degrade, low mechanical strength | Acts as natural scaffold and promotes cell attachment and bone formation |

Hyaluronic acid | Animal tissue | High biocompatibility, low porosity, can take weeks to degrade, low mechanical strength | Enhances cell migration, differentiation, and tissue integration |

Silk fibroin | Arthoprods | High biocompatibility, moderate porosity, can take weeks to months to degrade, high mechanical strength | Strong and flexible; supports cell attachment and different; good for load bearing scaffolds |

Pectin | Fruit/vegetable waste and plant cell walls | High biocompatibility, low porosity, can take days to weeks to degrade, low mechanical strength | Forms gels for bioinks; supports nutrient transport |

Natural polymers are typically best for their biocompatibility and biodegradability, meaning they can safely interact with the body and naturally break down over time. They also contain biological molecules that support cell attachment, growth, and communication, making them excellent for tissue regeneration.

However, most natural polymers lack the mechanical strength and rigidity needed to support load-bearing bones on their own. Materials like collagen and gelatin are too soft and can deform easily under pressure. As a result, scientists are reinforcing them with synthetic polymers and ceramic particles, creating composite scaffolds that combine the biological properties of natural materials with the strength of synthetic ones.

Scientists are also using purely synthetic polymers because they can be customized to have specific properties such as high mechanical strength, adjustable porosity, and controlled degradation rates. Unlike natural polymers, their structure can be easily tuned to match the mechanical demands of different bones in the body.

Table 2. Synthetic polymers that are ideal for BTE.

Polymer | Source | Key Properties | Role in BTE |

Poly lactic acid (PLA) | Polymerization of lactic acid monomers | High biocompatibility, moderate porosity, can take months to a year to degrade, high mechanical strength | Provides structural support for scaffolds |

Polycaprolactone (PCL) | Synthetic aliphatic polyester | High biocompatibility, low porosity, can take 1-3 years to degrade, high mechanical strength | Flexible and strong; ideal for large of irregular bone defects |

Poly lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) | Copolymer of lactic acid and glycolic acid | High biocompatibility, high porosity, can take weeks to months to degrade, moderate mechanical strength | Controlled degradation scaffold; can deliver growth factors |

Poly 3-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) | Microbial fermentation | High biocompatibility, low porosity, can take months to a year to degrade, high mechanical strength | Often blended with other polymers to improve strength |

Poly vinyl alcohol (PVA) | Synthetic water-soluble polymer | High biocompatibility, moderate porosity, can take months to a year to degrade, moderate mechanical strength | Used for soft tissue-bone interfaces; used in bioinks |

Poly ethylene glycol (PEG) | Synthetic polymer | High biocompatibility, high porosity, can take months to degrade, high mechanical strength | Hydrophilic and often used as a coating; improves nutrient transport and tissue integration; can be functionalized to carry bioactive molecules |

Polyurethane (PU) | Synthetic polymer | High biocompatibility, moderate porosity, can take months to degrade, high mechanical strength | Provides elasticity and mechanical resistance |

After the selection of polymers, 3D printing strategies are used to fabricate scaffolds with precise shapes and internal structure. By adjusting printing parameters, researchers can design scaffolds that replicate the structure and strength of natural bone. 3D printing also makes it possible to create patient-specific implants based on medical imaging data, improving the fit and integration of the graft once implanted.

Printing Methods

Currently, there are three main printing technologies being used: Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF), Direct Ink Writing (DIW), and Selective Laser Sintering (SLS). Each of these techniques have their advantages and limitations:

FFF: This 3D printing method uses thermoplastic polymer filaments, which are melted and deposited layer by layer to create 3D objects. FFF is widely used in large-scale additive manufacturing because it offers fast printing speeds, high precision, and relatively low operational costs. However, its high printing temperatures can damage the biomaterial. Additionally, its nozzle size and polymer flow rate limits the creation of porous implantable structures.

DIW: This technique heats polymer pellets until they melt into small droplets, which are then pushed through a nozzle using a screw system or compressed air. DIW allows for accurate placement of polymers, bioactive molecules, metallic particles, and even living cells, making it a versatile method to create scaffolds. However, DIW requires a high operational cost and involves complicated machinery. The method of extrusion usually leads to a lot of waste and contamination.

SLS: In this method, a CO2 laser heats polymer powders in specific areas based on a digital design. These powders then cool down and fuse with each other to form a structure. The laser scanning allows for high fabrication speeds and detailed designs with high accuracy. This method is also very costly because of its inability to recycle the materials and the structures lacking mechanical strength.

Applications

The most common use for 3D-printed polymeric biomaterials is to create personalized scaffolds for bone repair. By using CT/MRI imaging data, implants can be designed to the exact size and shape of a patient's bone defect. These imaging techniques provide high-resolution, 3D maps of the damaged area, allowing engineers to create an implant that fits perfectly with the surrounding bone. The high precision ensures that the implant is stable, aligned, and fully integrated into the environment by reducing any gaps or pressure points that could prolong the healing process. Patient specific customization becomes crucial to complex or unusual bone defects since traditional grafts or metal implants may not conform properly to the defect site. Once the 3D printed implant has been attached, it will replace the damaged bone tissue for a temporary period of time and provide an environment that encourages bone growth.

While many of these scaffolds serve primarily as structural supports, recent advances have transformed them into bioactive structures: constructs that actively promote biological regeneration. By integrating molecules such as growth factors, hormones, extracellular matrix components, and other signaling molecules, these scaffolds interact with the surrounding cells to advance the healing process.

This technology is also beneficial for precise drug delivery. 3D-printed nanoparticles are used to deliver hormones, biological factors, and live cells to bone defect areas. Their design allows them to reach their target location at the defect site and facilitate bone regeneration.

What’s Next: The Future of Bone Regeneration

Although 3D printed polymeric biomaterials show a lot of potential for clinical applications, there are still some limitations. This is mainly due to the fact that bone tissue is a very complex structure and 3D printing technology isn’t capable of replicating all of its dimensions. Additionally, even though customized implants can be made from 3D printers, bone defects are always changing over time. As a result, the actual surgical procedure can be jeopardized.

In order to overcome this, scientists are looking into in situ printing, where the cells and scaffold will be directly added to the defect site during surgery. This would eliminate the risks of the implant not matching the defect.

In the future, AI will also become an integral part of the BTE process. AI will be able to help engineers create efficient designs by predicting the mechanical strength and rate of degradation. They would also be able to create databases that compile relevant data that would make the process of choosing polymers much easier.

The journey toward fully restoring bone tissue is still ongoing, but by customizing 3D printed polymeric scaffolds, medicine is one step closer to that goal.

.png)